UM6P Discovers the Long Reach of Plastic Pollution from the Heart of the High Atlas

You can stand at 4,167 meters on Mount Toubkal and believe you have escaped everything human. UM6P’s new study, the first high-altitude assessment of its kind in North Africa, shows the opposite: even this harsh, ancient terrain now carries the fingerprints of drifting plastic fibers, offering a new blueprint for environmental research. Mohamed Idbella, a microbial ecologist at UM6P, works within the AgroBioSciences (AgBS) program at UM6P College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences. His work focuses on understanding microbes, the tiny life forms that play essential roles in soil, water, and ecosystems, including inside our bodies.

Mount Toubkal, the highest peak in North Africa, became for a team of researchers from University Mohammed VI Polytechnic a 4,167-meter-long scientific instrument. By systematically analyzing soil from its base to its summit, they produced a clear, data-rich snapshot of how human-made materials travel and settle in one of the continent’s most remote environments.

The study, led by Dr. Mohamed Idbella, was designed to move beyond simply confirming pollution and instead examine the mechanics of its distribution and impact.

The team collected soil samples from nine elevations, ranging from 500 to 4,167 meters. In the laboratory, they combined established and advanced techniques: particles were separated, counted, and categorized; polymer types were identified using FTIR spectroscopy; and electron microscopy was used to examine particle surfaces and assess their environmental history.

A Distribution Curve That Tells Two Stories

The data revealed a distinct U-shaped curve in microplastic concentration. Levels were higher at the mountain’s base, lower in mid-elevation forests, and high again near the wind-scoured summit.

This U-curve represents two dominant transport mechanisms. The first peak is terrestrial and local, reflecting nearby human activity: agricultural plastic mulches, road wear, and settlement litter.

The second peak, observed at the summit, is atmospheric and regional. Particles found above 4,000 meters were overwhelmingly small (under 500 micrometers) and composed of low-density polymers such as polystyrene and cellulose acetate. Under SEM-EDX analysis, their surfaces showed extensive weathering.

“The particles at the summit are not from a nearby bottle,” explains Dr. Idbella. “They are aerosolized, lifted by wind, potentially from cities hundreds of kilometers away. The high-altitude environment acts as a depositional sink, literally collecting a sample of what circulates in the air column over North Africa.”

This finding reinforces the role of remote mountains as active monitors of long-range atmospheric pollution, aligning with evidence from regions such as the Himalayas and the Andes.

Measuring the Biological Response

A defining strength of the study is its integration of physical analysis with a biological investigation. From each soil sample, total DNA was extracted and sequenced, targeting the bacterial 16S rRNA gene and the fungal ITS region. This enabled a complete census of microbial communities at each elevation.

The results were nuanced and revealing. Bacterial communities, known for their diversity and metabolic flexibility, showed no statistically significant changes in diversity or composition related to microplastic abundance, polymer type, size, or shape. This highlights their remarkable resilience.

Fungal communities, however, told a different story. Statistical analysis showed that fungal richness and diversity were negatively correlated with the presence of specific microplastic types—particularly synthetic fibers and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) particles. Where these materials were more abundant, fungal diversity declined.

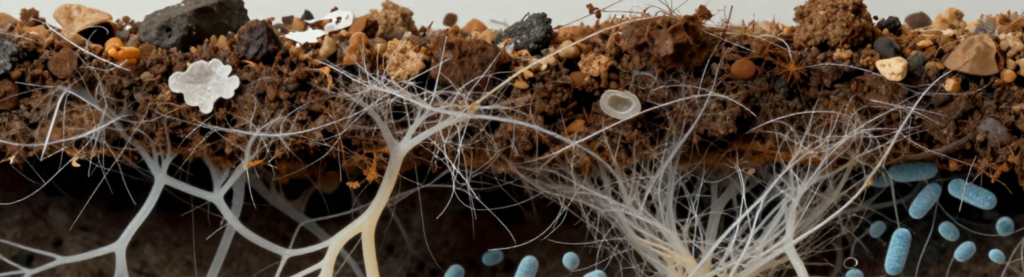

The explanation lies in fundamental biological differences. Fungi are sessile, filamentous organisms that grow by extending hyphae through soil pores, forming networks essential for nutrient cycling and organic matter decomposition.

“Synthetic fibers alter the soil’s physical architecture,” says Dr. Idbella. “They can obstruct hyphal growth, like fine netting. Polymers such as PVC may also leach chemical additives, including plasticizers, which some fungi are sensitive to.”

Bacteria, being smaller, unicellular, and mobile, can adapt more easily to these altered conditions.

This reveals a process of selective pressure: microplastics act as an environmental filter, reshaping microbial communities over time. In the nutrient-poor, high-alpine environment, such changes could influence soil fertility, decomposition rates, and ecosystem functioning.

A Model for Integrated Research

The Toubkal study carries broad implications for both environmental science and research practice.

First, it provides a trait-based framework for ecological risk assessment, demonstrating that microplastic impact depends not only on quantity but on particle properties—including polymer type, size, shape, and weathering state.

Second, the study exemplifies integrated, institutionally supported science, requiring collaboration across soil science, analytical chemistry, materials imaging, and molecular biology, supported by advanced instrumentation.

“This work was enabled by an ecosystem that supports interdisciplinary inquiry,” says Dr. Idbella. “It’s a blueprint for building research programs that address both local and planetary challenges.”

Finally, the research establishes a critical baseline for the Atlas Mountains, a region vital for water resources, biodiversity, and climate resilience. Mount Toubkal is transformed from a passive landscape into an active sentinel site.

The team views this as a foundational dataset. Ongoing work includes studying seasonal and annual deposition fluxes and investigating whether microplastics act as vectors for other contaminants, such as antibiotic resistance genes, potentially facilitating their spread across remote environments.

Want to dive more ?

Read the full article here.

Leave a Reply