At UM6P, a researcher is rethinking how renewable power stays stable when the grid no longer cooperates

For decades, power grids were designed under the simple assumption that the network would remain strong, predictable, and “stiff” from an electrical standpoint. That assumption is now eroding. As renewable energy spreads across weaker and more variable grids, stability has become less a matter of hardware and more a question of control. At UM6P, that quiet failure has become the focus of new research into how renewable energy meets the grid.

For Youssef Lamkharbach, an Education Fellow at UM6P’s Green Tech Institute (GTI) and a PhD researcher focused on grid-connected photovoltaic systems and their stability under weak-grid conditions, that question is not just theoretical. It appears as resonance oscillations in systems using LCL filters, as controllers that behave well in simulations but struggle in real conditions, and sometimes as protective shutdowns triggered not by major faults but by instability risks under weak-grid conditions.

Today, many of the “obvious” barriers to the energy transition have been reduced. Solar panels are more affordable. Batteries are more capable. Inverters are faster and more efficient. Yet as renewable generation expands across grids that were not originally designed for high shares of power-electronics-based sources, a more subtle question increasingly dominates engineering discussions: how can grid-connected inverters remain stable when the grid becomes weak or uncertain?

“In the past, the grid was something you could almost take for granted,” Lamkharbach explains. “But in weak-grid situations, the grid actively influences the converter dynamics — and the control system must be designed with that reality in mind.”

That shift — sometimes gradual, sometimes sudden — is pushing researchers to revisit how renewable energy systems are controlled, especially at the thin boundary where digital control, sampling delays, and power-electronic switching interact with real-world grid impedance.

The problem hiding in plain sight

Behind every grid-connected photovoltaic inverter sits a filter whose job is quiet but critical: shaping the output current so that high-frequency switching harmonics do not pollute the grid. In many modern designs, that filter is an LCL network—a compact and efficient combination of inductors and a capacitor. But this efficiency comes with a known trade-off: it introduces a resonance peak that can threaten stability if it is not properly damped.

“An LCL filter is very good at cleaning the current,” Lamkharbach explains. “But it introduces a resonance that sits right where the controller is trying to work.”

In traditional grids – dominated by large synchronous generators – that resonance is relatively easy to manage. The grid behaves like a stiff voltage source, and its impedance is relatively low and predictable. But in weak-grid conditions—for example in remote networks or areas with high penetration of inverter-based generation—that assumption no longer holds.

“As the grid impedance increases, the resonance frequency and the overall dynamics change,” he says. “And when the dynamics change, the stability margins of the controller can shrink.”

The result is a growing class of systems that are compliant on paper, but fragile in practice.

Why damping stopped being simple

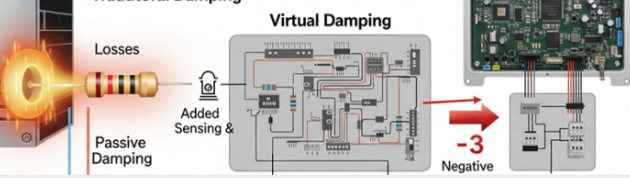

The classical response to LCL resonance is damping. Early grid-connected inverter designs often relied on passive damping, typically by adding resistors to dissipate energy and suppress oscillations. This approach is simple and robust, but it comes with a clear trade-off: extra losses, more heat, and reduced efficiency—precisely what modern renewable-energy converters try to avoid.

To overcome these drawbacks, active damping became a widely adopted alternative. Instead of dissipating energy through hardware, the controller uses feedback to create a “virtual damping” effect—shaping the control action so the inverter behaves as if a damping resistance were present.

“But active damping is only as effective as the feedback signal and the way it is processed,” Lamkharbach notes.

Many established strategies are based on capacitor-voltage or capacitor-current feedback, often combined with high-pass filtering, or on indirect feedback signals measured on the inverter side. These methods can work well, but in digital implementations they face three recurring limitations.

The first is added sensing and complexity. Some active damping schemes require measuring additional variables—such as capacitor current or capacitor voltage—which may not be available in standard low-cost inverter platforms.

The second is noise sensitivity. High-pass filters naturally emphasize higher-frequency components—the same frequency range where switching ripple, sensor noise, and quantization effects are more pronounced.

The third is digital delay. Sampling, computation, and PWM introduce phase lag. As frequency increases, this phase lag can significantly reduce damping effectiveness and, in some cases, cause the active damping action to behave like negative damping—meaning the controller unintentionally reinforces oscillations instead of suppressing them.

“When that happens,” Lamkharbach says, “you’re no longer damping the resonance. You’re feeding it.”

This creates a practical limitation: conventional active damping strategies may lose robustness well below the Nyquist frequency, especially under weak-grid conditions where the system dynamics are more sensitive to impedance variations.

A modest change with disproportionate effects

The work carried out at UM6P does not try to overcome these limitations by adding more sensors or increasing computational burden. Instead, it revisits an assumption that had gone largely unchallenged: that active damping must be built around high-pass filters.

“What we found,” Lamkharbach explains, “is that the shape of the feedback matters more than its order.”

By replacing the high-pass filter with a band-pass filter, and discretizing it using a Tustin pre-warping method, the feedback signal acquires an unexpected property. Near the Nyquist frequency, its gain becomes negative rather than positive.

“This means the controller stops listening to noise,” he says, “instead of amplifying it.”

Treating delay as a first-class citizen

Rather than approximating or neglecting it, the UM6P approach incorporates a full delay compensation block directly into the active damping loop. The compensation is based on a modified first-order digital filter that counteracts the phase lag introduced by sampling, computation, and PWM actuation.

“We’re not eliminating delay,” Lamkharbach says. “We’re designing around it.”

With compensation, effective damping extends to roughly 0.455 times the sampling frequency, well beyond the practical limits of conventional methods.

Stability as a moving target

Instead of validating the controller only at one nominal point, the analysis examines how stability evolves when key parameters vary—such as grid impedance (grid inductance), active damping gain, proportional gain, and the resonance frequency of the LCL dynamics.

“In real installations, parameters do not stay fixed,” Lamkharbach explains. “If a controller is stable only for one ideal case, it won’t be reliable in practice.”

The results reveal wide stability regions, even as grid inductance increases toward values representative of weak or remote networks.

Why this matters beyond the lab

For manufacturers of photovoltaic inverters and battery energy storage systems, the implications are practical. When active damping remains effective over a wider frequency range, designers gain more flexibility in LCL filter design. In many cases, it becomes possible to reduce filter size while maintaining stability and grid-code compliance.

Importantly, the proposed strategy is built on grid-current feedback, a measurement already available in most standard inverter platforms. No additional sensors are required.

“It’s a control solution, not a hardware one,” Lamkharbach says. “That’s where scalability comes from.”

For system operators and end users, the benefits include fewer unexpected disconnections, smoother behavior during grid disturbances, and more reliable operation in weak-grid environments. Over time, improved stability can reduce stress on components, contributing to longer equipment lifetime and more dependable renewable energy services.

Want to dive more ?

Read the full article here.

Leave a Reply